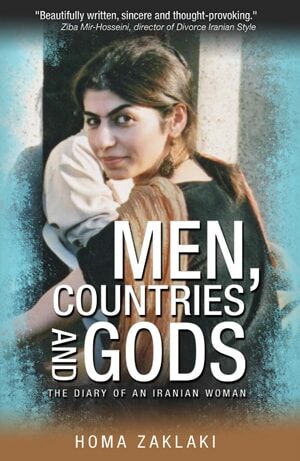

As I read the letter, I felt a swelling of disappointment but not even a tinge of surprise: “Though it seems like it will be a great read, I didn’t connect with it,” read the response of the representative of a renowned agency in reference to the submission of our first novel, “Men, Countries and Gods – The Diary of an Iranian Woman”.

There is probably no writer who has not received a letter from a literary agent reassuring them that the rejection of their work is primarily based on two reasons: firstly, the competitiveness of the market and secondly, the agent’s personal taste.

There is indeed competition in the market; it’s a contest for the story that becomes “knowable” amidst many. Those few stories that are institutionally validated turn into a credible narrative, the central story that marginalises the vast majority of all other alternative stories. However, any critical reader would agree that – as feminists say – personal being political, there is nothing simple and pure about our taste of literature and preference for stories. The ‘personal taste’ often is a shorthand for a political agenda, one that promotes the dominant, privileged perspective and hinders others’ voices from being heard. There is nothing personal about the selection of a master narrative.

Stories are the vessels of knowledge, and knowledge, we are told, is power. We seek stories from our specific socio-political and cultural standpoint to help support our worldview. Our taste is not a pre-given thing; it is a reflection of cultural norms. Michele Foucault, the French philosopher, is well-known for his work on power-knowledge dynamics. He argues that social practices of control and supervision produce a particular form of knowledge centered on specific ideas and beliefs. In simple terms, related to our discussion here, agents and publishing houses are implicated in producing certain books as well as shaping readers’ views, aesthetics and expectations.

This notion of stories being products of a power-knowledge interaction has even more far-reaching consequences in the context of a non-western narrative, a Muslim woman’s story in our example, seeking recognition in mainstream Western publishing.

In his most influential book Orientalism (1978), Edward Said, an Arab-American intellectual, examines the representation of the Orient in Western fiction and non-fiction writings. He looks on Orientalism as a story, a powerful fiction that produces statements about the Orient. Orientalism, in his view, is a certain knowledge of the Orient that was invented by the West according to its sentiments and in service of its own power interests. By power, he is not only referring to political power, but he is also referring to the intellectual and cultural superiority of the West: the West’s language, traditions, lifestyle, costumes, art and taste. The knowledge of the Orient is constructed by previous readings of texts on the Orient, conceptions and fantasies. Ultimately, the encounter with the Orient is never neutral and balanced.

Consequently, in society, certain kinds of culture and knowledge are supported and privileged. In other words, an agent contacted by me is in possession of knowledge about my book on the thoughts and experience of a woman from the Middle East even before she reads the first page of my manuscript. It is a knowledge that precedes the narrative. Hence, having accumulated a series of accounts and understandings about the Orient, literary agents, publishers and readers open a book in search of confirming what they believe they already know on that matter.

This is not a simple thing, the Other is needed to create oneself. Our identity and sense of ‘self’ hinges on the Other accepting his proper place, an unspoken but clearly delineated place. The perception of oneself is embedded in the portrayal of the Other. Any distortion in the Other leads to a distortion of ‘self’. Any alteration in the story of the Other questions the ‘self’. Any rewriting of the Other poses a violation to the world of ‘self’. Thus, Edward Said argues the difficulty, if not the impossibility of producing a different work on the Orient.

Similarly, Gayatri Spivak, an Indian feminist and literary theorist, contends that the ethnocentric Western listener puts places the Western subject at the centre because the West is only interested in itself as the subject of knowledge. The West silences the subaltern, the second class disenfranchised group. There is no one to listen to them since the listener is the elite, reluctant to change. His ability to truly listen is limited by his geo-political location and Eurocentric values. Still, the West lets in a few special outsiders from the margins be the representative of the voice of the Others. To let them in is necessary for its own existence; society needs a foil against which to frame their perceived superiority. Hence, Spivak’s provocative statement: ‘the subaltern cannot speak’ (1988).

A well-intentioned academic friend and writer has been trying for years to coax me into writing about my Iranian family because, he explains, it would be more likely to bring me commercial and literary success than my current book about a Muslim woman that doesn’t fit into the Western repertoire of knowledge and imagination on the subject. What I want to be known about me is not as important as what the West wants to know about me.

Literary norms are established through reiteration, through the unconscious act of generating the same script with different actors, again and again. Therefore, my friend’s advice and the agent’s taste tend to perpetuate familiar narratives and power dynamics. Happily, self-publishing offers an opportunity to introduce multiple and heterogeneous voices to the market. Self-publishing gives us at least a shot at leveling the playing field between West and East when it comes to cultural power.