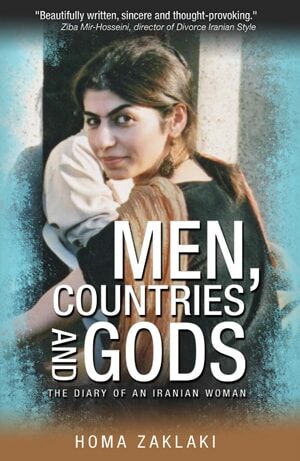

Tell us about your book

Roghieh: In brief, the book is about a young woman’s reaction to uprooting in her childhood and the subsequent sense of estrangement in the world. We follow her journey as she fumblingly navigates her way ‘home’. And she happens to be Iranian, which of course colours her experience of the world in a unique way.

Leila: The story of an ambitious woman with more plans than dreams until life forces her to expand.

How much of this book is based on your own life experiences?

Leila: As a rule of thumb: what you like about the protagonist is autobiographical and what you hate about her, is all fiction.

Roghieh: I’d like to look at it like a painting; the mood, the colours and the canvas are based on our own life, but the patterns, shapes and images created are all fiction.

Can you tell us something of your own life stories?

Why did you choose diary format to tell Solmaz’s story?

Roghieh: The diary is for me a feminine form of expression. It is honest, naked and non-linear. There is this earthly quality to it that I didn’t feel capable of producing in any other form.

Leila: In fact, we tried other formats – first-person, third-person narrative, and even a mixture of both – but diary was the only way to dive deep enough without compromising the narrative.

The book spans two years of Solmaz’s diary entries. To what extent would it be true to say that this is a period of “growing up” for her?

In Bangladesh, Solmaz witnesses terrible poverty and suffering in both urban and rural populations. How true to life is the representation in the book?

In conversation with Belal, Solmaz says “…Arranged marriages can work out as much as love marriages can fail”, while confiding in her diary that she doesn’t really believe this. Does the fact that Belal’s marriage was an arranged one make it easier for her to overlook the fact that he is married?

Born in Iran, brought up in Vienna and living in London, Solmaz never feels entirely at home in any of them. Does her time in Bangladesh, where she is truly a foreigner, change this?

What were the challenges in writing in a foreign language?

Roghieh: A piece of cake. As a woman I feel I don’t do anything but treading on “foreign“ lands, speaking “foreign“ languages and worshiping “foreign“ Gods anyway. That is indeed one of the main messages of the book.

Leila: Not having a truly native language, English is for me the most natural language for writing. When you think of it, our years of so called “intellectual development“ happened in Austria and the U.K., reading and writing in German and English.

How did you tow collaborate in writing the book? Do you argue a lot over the writing?

Leila: Oh, my God. Hell. Working with Roghieh was hell. I lost track of how many times I said: Never again.

Roghieh: No pain, no gain.

Kindle edition and paperback available on Amazon